A weekly review isn’t only a retrospective, but a prospective too. It lets you run through the upcoming Monday to Friday and get prepared in advance. You’ll start each day armed with the game plan that you created during your weekly review. Proactively planning for the week ahead doesn’t mean scheduling every single thing you’ll need to do. The new decree establishes that the curfew in the national territory will be from Monday to Friday from 10:00 p.m. And on Saturdays and Sundays from 9:00 p.m. “In the same way, it also explains that there will be a grace of free movement until midnight every day, with the sole purpose that people can go to their. Edit: I asked the Todoist team on their website, and quickly got a response. The solution to my problem was: 'every Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday'. Can't believe I didn't think of that. I'm trying to set a 'get the mail' task. I can't for the life of me figure it how to make a task for every weekday and every Saturday.

Albanian adopted the Latin terms for Tuesday, Wednesday and Saturday, adopted translations of the Latin terms for Sunday and Monday, and kept native terms for Thursday and Friday. Other languages adopted the week together with the Latin (Romance) names for the days of the week in the colonial period. For a Monday-Wednesday-Thursday-Friday class, make sure your meeting start date is a Monday. From the recurrence drop-down menu, select Weekly. The menu will state 'Occurs every Monday starting your start date.' Now select Custom from the recurrence drop-down menu. A custom recurrence prompt appears. Keep M for Monday selected.

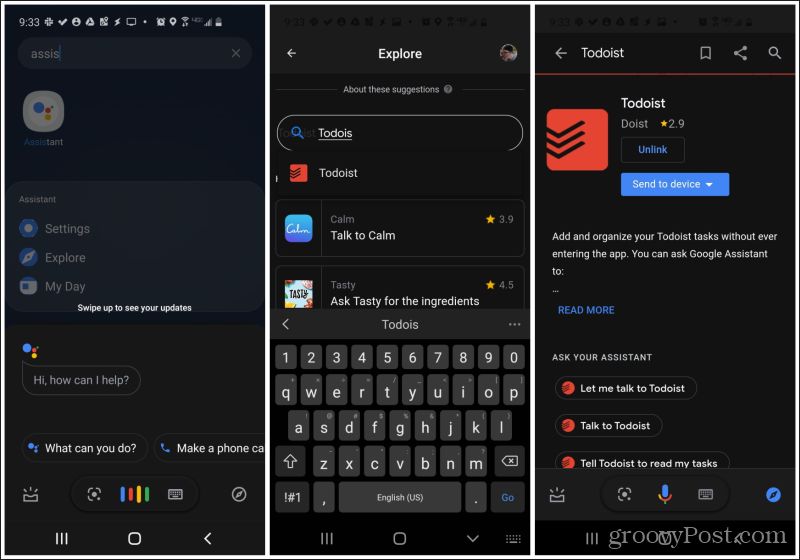

Some people get a thrill from checking items off a hand-written to-do list. Others prefer to manage their lives with feature-packed digital calendars. I am both, and when I discovered Todoist earlier this year, it seemed like the best of both worlds: the ease of managing tasks in a centralized app combined with the simple pleasure of marking tasks off when you finish them. Now Todoist is even better with a facelift that delivers a new look and even more helpful new features.

The popular task management app on Tuesday rolled out a brand new version for iOS that sets the stage for a dramatic, platform-wide overhaul. Some 4 million people use Todoist to add 510,000 projects daily, and share an average of 52,000 tasks a day across millions of projects. Todoist founder and CEO Amir Salihefendic told me his team has been working to make the task management tool’s mobile apps as powerful as its desktop version, and with version 10, they have finally succeeded.

“A few years ago. you could only do a simple list and nothing else,” Salihefendic said. “Now we have made the mobile apps as powerful as our desktop apps, and I think they are easier to use and more intuitive.”

A slew of new (free!) features

There are immediately obvious changes: Version 10 gives Todoist a makeover that makes every interaction cleaner and simpler to use. There are also now 10 themes to choose from, so you can swap in tangerine, blueberry, or a neutral shade for the Todoist red.

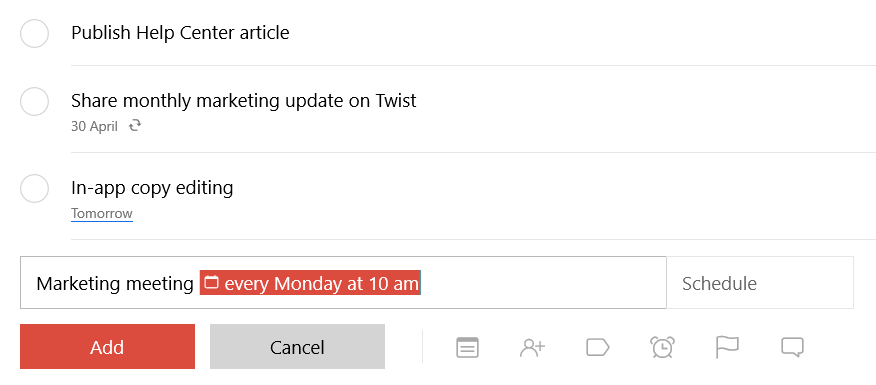

But the new Todoist for iOS goes beyond a fresh face. The app’s new features are subtle but convenient. The two biggest changes are multi-task editing, which lets you change due dates, delegate, and move multiple tasks from one project to another, and more intelligent scheduling, so you can create tasks with unique start and end dates like, “Run 5 miles every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday at 7 a.m. from May 1 through November 1.” Todoist has always been able to parse deadline dates/times as you type, but now it’s even smarter—and the app’s in-line adding can recognize 10 languages.

Todoist’s overhauled date-parsing is one of the features that will take time for its users to discover, but it’s also what sets the app apart, Salihefendic said. More than 50 percent of Todoist tasks include dates, so the company decided to make those dates “much more powerful” in a way that no other to-do list app has done.

Another new feature is one I didn’t even realize I wanted until I had it: the ability to pull apart two tasks to add one in between. You can also use a long press to reorder projects, move sub-tasks from one project to another, and collapse or expand tasks or projects.

All of the new features, minus a few of the themes, are available in the free version of Todoist. Premium users can pay $29 a year to unlock labels, task reminders, location reminders, calendar synchronization, productivity tracking, and the complete library of color schemes.

Chinese (Mandarin) currently has three sets of names for the days of the week. All are based on a simple numerical sequence.

Standard naming

The standard naming as taught to foreign learners and officially favoured in China itself is based on the word 星期xīngqī 'week', with the days ranged in a numerical sequence. The word 星期xīngqī literally means 'star period'.

| Sunday | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday |

| 星期日 or 星期天 | 星期一 | 星期二 | 星期三 | 星期四 | 星期五 | 星期六 |

| xīngqīrì xīngqītiān | xīngqīyī | xīngqī'èr | xīngqīsān | xīngqīsì | xīngqīwǔ | xīngqīliù |

| 'week day' | 'week one' | 'week two' | 'week three' | 'week four' | 'week five' | 'week six' |

In naming the days of the week, 星期 is followed by a number indicating the day: 'Monday' is literally 'week one', 'Tuesday' is 'week two', 'Wednesday' is 'week three', etc. The exception is Sunday, where 天tiān or 日rì both meaning 'day' (日rì is somewhat more formal than 天tiān) are used instead of a number. 'Sunday' thus literally means 'week day'.

(Note that, although 星期xīngqī has been standardised as xīngqī in Mainland China, the older colloquial pronunciation xīngqí is preserved on Taiwan. To hear how these names are pronounced, listen to these videos on Youtube: A — B — C, all somewhat overarticulated. Two videos, D and E, feature the Taiwanese Mandarin pronunciation as well as other names for days of the week, as outlined later in this page.)

This naming has three interesting features:

- The word for 'week', 星期xīngqī, is a mysterious term literally meaning 'star period'.

- Sunday is known by the almost meaningless name of 'week day' (or 'star period day').

- The numbering of days proceeds from Monday as the first day.

Original naming

In order to understand the origins of this naming, we need to look at another set of Chinese names for the days of the week, one that is not officially encouraged but is in widespread use, based on another Chinese term for the week, 禮拜lǐbài (礼拜 in its simplified form). The original meaning of 禮拜 / 礼拜lǐbài is 'worship'. This naming goes:

| Sunday | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday |

| 禮拜日 or 禮拜天 | 禮拜一 | 禮拜二 | 禮拜三 | 禮拜四 | 禮拜五 | 禮拜六 |

| 礼拜日 礼拜天 | 礼拜一 | 礼拜二 | 礼拜三 | 礼拜四 | 礼拜五 | 礼拜六 |

| lǐbàirì lǐbàitiān | lǐbàiyī | lǐbài'èr | lǐbàisān | lǐbàisì | lǐbàiwǔ | lǐbàiliù |

| 'worship day' | 'worship one' | 'worship two' | 'worship three' | 'worship four' | 'worship five' | 'worship six' |

(To hear the pronunciation, listen to the You Tube videos D and E.)

Substituting 'worship' for 'star period' reveals the logic of the naming. Notably, Sunday changes from the meaningless 'week day' into 'day of worship', providing a valuable clue to the origin of the naming. The use of 禮拜lǐbài / 礼拜 for the week is intimately related to the process whereby the Western-style week came into China.

Before they adopted the Western-style week, the Chinese used a ten-day cycle known as a 旬xún in ordering their daily lives and activities. Although the Christian week was not unknown (it was known, for instance, from contact with the Jesuits in the 16th-18th centuries), the seven-day week as we know it first became widely familiar in the 19th century with the coming of traders and missionaries from Western powers (Note: Christian missionaries in China).

The term 禮拜lǐbài / 礼拜 in the sense of 'week' first appeared in writing in 1828 and is likely of dialectal origin. A dictionary of Cantonese colloquialisms from that year, entitled 廣東省土話字彙Guǎngdōng-shěng Tǔhuà Zìhuì'Guangdong province colloquial vocabulary', gave 禮拜 as the equivalent of 'week' in English.

禮拜 / 礼拜lǐbài as a verb normally refers to worship as practised in the Christian and Muslim faiths. Its extension to mean 'week' appears to be due to local Chinese noticing that the Westerners worshipped every seven days. However, the specific mechanism by which this extension of meaning came about, and how the system of numbering the individual days developed, is not clear. It seems likely that the other days of the week were numbered off in sequence after the day of worship (Monday = 'day of worship plus one', Tuesday = 'day of worship plus two', etc').

Advent of the official naming

While 禮拜lǐbài'worship' was the most common word for 'week' (and remained so right up until the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949), it failed to find favour with literate Chinese for obvious reasons. Not only was it associated with Western imperialism and a foreign religion, it was likely seen as 'inappropriate' or 'plebeian' by the literate elite, whose focus was on classical Chinese and the written word.

The term 星期xīngqī'star period' in the sense of 'week' was first attested in print in 1889. 星期xīngqī was originally an old term for the 'Star Festival' (or 七夕qīxī), China's equivalent of Valentine's Day, which falls on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month. The repurposing of 星期Todoist Every Monday Wednesday Friday Holiday

xīngqī'star period' to mean 'week' was clearly influenced by the planetary names, in particular the old system of planetary names that had been introduced into China over a millennium earlier by the Buddhists. (Note: Is 'xingqi' a modern coinage?)Buddhist translators in the first millennium had created a set of names based on the nomenclature of the seven 'planets' — the Sun, the Moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn — using the terminology of the 'seven luminaries' or 七曜qīyào. The 七曜, like the 'seven planets', referred to the Sun, the Moon, and the five visible planets:

| Sunday | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday |

| 日曜日 | 月曜日 | 火曜日 | 水曜日 | 木曜日 | 金曜日 | 土曜日 |

| rìyào-rì | yuèyào-rì | huǒyàorì | shuǐyào-rì | mùyào-rì | jīnyào-rì | tǔyào-rì |

| 'sun luminary day' | 'moon luminary day' | 'fire (Mars) luminary day' | 'water (Mercury) luminary day' | 'wood (Jupiter) luminary day' | 'metal/ gold (Venus) luminary day' | 'earth (Saturn) luminary day' |

The story of how these names came to China, and then Japan, is told at Japanese days of the week. These names were still known in China during the Qing dynasty and appear to be the inspiration for adopting the term 星期xīngqī.

When the adoption of the Western week was announced after the fall of the Qing dynasty in the government gazette of 10 February 1912, the term used was 星期xīngqī. This was allegedly due to the support of the outstanding scholar 袁嘉谷Yuán Jiāgǔ, who is remembered for setting up a government department to supervise terminology in textbooks in 1909. 星期xīngqī went on to gradually gain in popularity, especially after the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949.

The adoption of 星期xīngqī instead of 禮拜 / 礼拜lǐbài did not involve a radical change; it simply substituted one word for 'week' with another. The original numbering system of 禮拜lǐbài remained intact. The main difference was the substitution of the meaningless term 星期日xīngqīrì or 星期天xīngqītiān'star cycle day' for 禮拜天lǐbàitiān'day of worship'.

Modern alternative naming

Given that the officially preferred naming involved nothing more than the substitution of one word for another, it is ironic that a third word for week has in recent times been making heavy inroads into the territory of 星期xīngqī. This is the word 週 / zhōu (simplified form 周), literally meaning 'cycle', which has given rise to a third set of names for days of the week:

| Sunday | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday |

| 週日 | 週一 | 週二 | 週三 | 週四 | 週五 | 週六 |

| 周日 | 周一 | 周二 | 周三 | 周四 | 周五 | 周六 |

| zhōurì | zhōuyī | zhōu'èr | zhōusān | zhōusì | zhōuwǔ | zhōuliù |

| 'cycle day' | 'cycle one' | 'cycle two' | 'cycle three' | 'cycle four' | 'cycle five' | 'cycle six' |

(To hear the pronunciation, listen to the You Tube videos mentioned above: D and E.)

The use of 週 / 周zhōu to mean 'week' appears to have entered Chinese from Japanese, probably around the turn of the 20th century. The earliest written references are from 1901 and 1903. The Japanese word 週shū'week' is itself of Chinese origin, having the meaning 'cycle'. The word fits quite naturally into Chinese and people are unconscious of its Japanese pedigree. One reason for the growing popularity of 週 / 周zhōu, especially among the educated urban classes, is the fact that it consists of only one syllable. Each day of the week becomes a comfortable two-character compound of the type favoured in Chinese.

As a result, Chinese now has three sets of names for the days of the week, based on three different words for 'week':

Todoist Every Monday Wednesday Friday Morning

- The official term is 星期xīngqī'star period', purportedly derived from the ancient Chinese seven-day planetary cycle.

- 禮拜 / 礼拜lǐbài meaning 'worship' is a common term for 'week' in everyday speech.

- 週 / 周zhōu meaning 'cycle' is a slightly more formal term that is gaining ground as a compact alternative to the other two.

While most days of the week have three possible names, Sunday has five due to the use of two words for 'day', 天tiān or 日rì.

All three sets of names can be heard in daily conversation, at times alternating in the speech of the same person. 星期xīngqī is the 'officially correct' term that is taught to foreign learners of Chinese. On the Mainland, 星期xīngqī and 週zhōu are the only forms acceptable in normal Chinese prose, in official announcements, and in other situations where 'standard Chinese' is required. When TV programs use subtitles to transcribe interviews with ordinary speakers, 星期xīngqī is commonly substituted where the speaker actually said 礼拜lǐbài.

In contrast, 禮拜 / 礼拜lǐbài is very common in informal conversation. It is said to be more popular in dialects in the south of China — some southern dialects use only the cognate of 禮拜lǐbài — and 星期xīngqī is said to be more popular in the north. Whether this is true or not, 礼拜lǐbài is in widespread use throughout China and Taiwan. Interestingly Cantonese speakers speaking Mandarin may consciously use 星期xīngqī as the 'correct' Mandarin form, in preference to the 禮拜 / 礼拜 of their own dialect.

Taiwan is less rigid in standardising 星期. Not only is 禮拜lǐbài commonly used in speech, it is also found in writing. An example can be found in the translation of Harry Potter into Chinese, where the Mainland versions stick to 星期xīngqī whereas the Taiwanese translation uses both.

Other namings

In addition to the three current naming styles, historically Chinese has had two other systems of naming.

One was the original planetary system that we noted above, based on the seven luminaries. Although the Chinese of the 19th century, with their prodigious written tradition, were still aware of the 'seven luminaries' nomenclature, unlike in Japan it never caught on as a way of naming the days of the Western-style week. Allegedly, the scholar 袁嘉谷Yuán Jiāgǔ decided against them because they were tongue-twisters in Mandarin, especially names like 日曜日rì yào rì. The planetary names enjoyed some currency during the period of Japanese aggression against China, having been attested to in school timetables of the 1920s or 1930s. However, they never came into wide usage and were perhaps too closely associated with Japanese imperialism to be palatable to most Chinese.

A second system was used at one stage by Chinese Catholics in accordance with the favoured naming of the Catholic church. (I have been unable to confirm whether this nomenclature dates from the time the Jesuits were active in China in the 16-18th centuries or is a later development).

| Sunday | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday |

| 主日 | 瞻禮二 | 瞻禮三 | 瞻禮四 | 瞻禮五 | 瞻禮六 | 瞻禮七 |

| 主日 | 瞻礼二 | 瞻礼三 | 瞻礼四 | 瞻礼五 | 瞻礼六 | 瞻礼七 |

| zhǔrì | zhānlǐ-èr | zhānlǐ-sān | zhānlǐ-sì | zhānlǐ-wǔ | zhānlǐ-liù | zhānlǐ-qī |

| 'Lord day' | 'observe-ritual two' | 'observe-ritual three' | 'observe-ritual four' | 'observe-ritual five' | 'observe-ritual six' | 'observe-ritual seven' |

These names are based on the word 瞻禮zhānlǐ ('observe-ritual', simplified 瞻礼). In Chinese, 瞻禮 / 瞻礼 zhānlǐ is used both for observances of the Buddhist religion and for 'feasts' of the Catholic calendar, such as the Assumption, Easter, the Pentecost, etc.

Both the numbering (with Monday as the second day) and the use of a term referring to 'feast-days' is a faithful reflection of the liturgical week of the Roman Catholic Church, which takes Sunday as the 'Lord's Day' and then numbers the weekdays as 'feast-days' or feria, Monday being the second feria, Tuesday the third, Wednesday the fourth, etc. The term feria originally meant 'free days' in Latin, but later came to mean 'feast days' and then, for some unknown reason, came to be applied to the days of the week (Note: The feria). This system of naming was adopted by the Vietnamese but does not appear to have been seriously entertained in China.

I would particularly like to acknowledge my debt to The Origin of names of days of the week in Chinese (in Chinese) for allowing me to add considerable additional information to the above account.

| Western Japanese Chinese Vietnamese Mongolian Summing up Web Links |